"Strange Sounds," Indeed...

After we got home from the tour of '89 (see previous posting), we all spent Christmas with our families and didn't speak to one another too much. We were physically and emotionally exhausted, and, I'd say, just plain tired of one another. I personally had no idea what would happen next. For all I knew, we were finished as a band. The $20,000 debt loomed, and I figured that we'd just spend the next year or two applying most of our gig income towards paying it off.

Somewhere around New Year's Day, 1990, I got a call from Ken, who told me that a deal had been arranged by Chuck to give Cooking Vinyl, our label in England, a new acoustic album, in return for debt payoff. This was fantastic news. We had wanted to record as the Death Valley Boys for a while, and this was a tremendous opportunity. On the '89 tour we had attempted to record a live acoustic album at one of our London shows, but it was pretty much a disaster. We were off our stride musically, we tried to pull too many new songs together at the last minute, and it was for me personally, one of the worst nights of my life as a musician. I felt like I was playing my clarinet with mittens. Even worse, the attempted recording sounded horrible, to the extent that our soundman Carl's board tape on cassette was far better than the "professional" one. The suits at Cooking Vinyl were somehow pleased with this sonic catastrophe, and would have released it, but Chuck said no, we'd record a new album instead. We made plans to record in February of 1990, at Gary Holt's studio in Mount Morris NY. We had recorded 'Why Should I Stand Up?' there, we liked the studio, and Gary was an excellent engineer and musician himself.

One of the unusual aspects of this particular album is that the horns were recorded entirely separately from the rest of the tracks. In fact, Joe and I never saw Phil, Jimmy or Ken in the studio even once on this session. Joe worked out the bulk of the horn arrangements on his piano at home, and he and I put them together in the studio. I play clarinet exclusively on this album, and Joe expanded his range of trombone colors by using a different mute on nearly every track. Chuck attended all of these sessions to approve the arrangements and our playing, but mostly he was astonished at the brilliance of Joe's parts, which were elegant and tasteful, and complemented the songs perfectly, without getting in the way of anyone else's tracks. I think that we were able to do this because we understood one another's playing extremely well by then, and had reached a higher level of musicianship from all of the touring. We were scary tight.

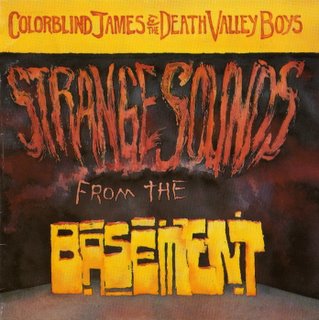

We recorded this album in about a month, working on it on nights and weekends, for a sum of (I think) around $2500. (This is probably what other bands would spend on pizza and beer in the same amount of time...) When it was done, I think we all felt a satisfaction that we'd done something truly unique. Scott Regan responded with what is IMHO our finest, most beautiful album cover. If there is a CbJE masterpiece, for me this is it. I would not presume to speak for the other band members, but this, in my opinion, is CbJE's most consistent, coherent and sophisticated album ever. Every track is worthy, contributing mightily to the sum. The recording quality is superb, in spite of the modest means, and we were all in peak form as musicians.

There are many fantastic moments, but I'll mention a few of my favorites: Phil's amazing double-tracked mandolin solo on "Don't Be So Hard on Yourself," his slide guitar on "Colorblind's Night Out," the lush sound on "O Sylvia," the three-minute miracle that is "Two-Headed Girl," and the lazy, loping ease that we have on the title track. The collective timekeeping of Chuck, Ken and Jimmy achieves a transcendental perfection. Joe's horn arrangements glow throughout, and the band's total musicianship is both astonishing and artfully concealed all at once. I'll make further comments on the songs themselves in a future posting.

And how was this masterpiece greeted by our record company? With bafflement, irritation and overall dis-interest. The album was never even released in the USA. Cooking Vinyl pressed up 2500 copies (LP, cassette and CD, in total) and did nothing discernable to promote it. When the first pressing sold out, there was no discussion of doing more. I never read a single review of this album, positive, negative or in between. The bitter irony for us was that we'd delivered a truly wonderful album, instead of the dreadful live thing that they originally wanted to issue. That our record company failed to see the difference in quality made this all the more painful. I always thought that the album would find an audience eventually, but I'd say the odds are pretty long at this point. Still, it's a recording that when I pull it out and play it, I feel pretty damn lucky to have been a part of it.